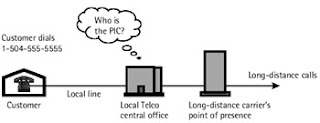

Long-distance calls are either billed as switched or dedicated. Most phone calls are switched. All residential calls are switched calls. Figure 1 shows how a switched long-distance call works. When a caller dials a long-distance number, the local carrier’s central office interprets the “1 + area code” that was dialed and then switches the call to the long-distance carrier’s nearest point of presence. The long-distance company then carries the call across its network. On the long-distance carrier’s bill, this call will show up under the heading “Switched Long Distance.”

The term “switched” refers to the fact that the first leg of the call was switched at the local carrier’s central office. This also means the long-distance carrier is paying access fees to the local carrier for this call. Figure 1 shows how the access fees are charged on a long-distance call. For this reason, switched long-distance rates are normally 3 to 4 cents higher than dedicated long-distance rates. If the access fees could be avoided, then the long-distance rates the customer pays should theoretically be 3 to 4 cents lower. This is precisely the reason why dedicated long-distance rates are lower than switched long-distance rates.

Dedicated long-distance service uses a T-1 circuit from the customer’s premise that connects directly through the long-distance carrier’s point of presence. This dedicated line carries all of the voice long-distance calls. The calls bypass the local carrier’s network, so the long-distance carrier does not pay access fees for these calls, which results in lower rates for the customer. Figure 2 illustrates how a dedicated long-distance call works.

Although the long-distance rates decrease with dedicated service, the customer will have the added monthly expense for the T-1 circuit. Even though the local carrier provides the physical circuit, the T-1 is usually billed by the long-distance carrier. The long-distance carrier will charge a fee for securing the T-1 facility from the local telephone company. This fee is usually called “access coordination” and costs about $85 per month. T-1 monthly costs range from $250 to $1,200 per month, depending on the mileage from the central office and the discount amount. The greater the mileage, the greater the cost.

T-1 installation

The one-time initial T-1 installation typically costs $1,000. The long-distance carrier will normally waive the installation cost if the customer has some negotiating leverage. If you are a new customer with the carrier, it will almost always waive the cost of installation because it is eager to win new business. If you have had any recent billing errors or service issues, carriers will almost always consider your inconvenience and waive these charges.

Beware, however, that your long-distance carrier representative normally only quotes the installation costs associated with the T-1 line. He probably does not have the expertise to determine whether or not your telephone equipment will be compatible with that T-1 line. Prior to placing any orders with your long-distance carrier, it is imperative that you consult with your equipment vendor.

In some cases, the telephone equipment may need costly upgrades that could make the project cost prohibitive. If the equipment only needs minor upgrades, the long-distance carrier may issue an invoice credit to cover the expense of the new equipment.